James Springer White (1821–1881) was a key figure in the Seventh-day Adventist Church and the husband of Ellen G. White.

He played an active part in the Millerite Movement, waiting for Jesus to return in 1844. When this didn’t happen, he joined with other Millerites, including his wife, to continue studying Scripture and eventually begin the Adventist Church.

Though sickly from childhood, he was a driven man who perhaps accomplished more in the history of Adventism than any other individual.

Here’s what we’ll cover about his life:

- An overview of James White’s early life

- James White’s life after the Great Disappointment

- James White’s role in the Adventist Church

Let’s get a glimpse of his earlier years and how they shaped his ministry.

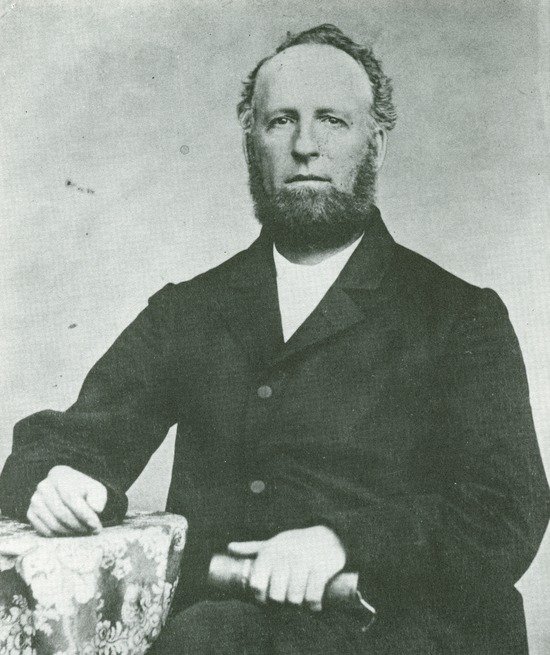

James White’s early life

Courtesy of the Ellen G. White Estate, Inc.

James White was born on August 4, 1821, in Palmyra, Maine. He was one of the nine children of John White and his wife Elizabeth—godly people who modeled Christian values to their children. He was baptized into the Christian Connection movement at the age of 15.1

But from the beginning, he struggled with his health. Severe illness at three years old left him with terrible eyesight so that he couldn’t read or attend school for many years.2

For someone like James with an insatiable love for learning, this was incredibly discouraging!

But finally, when he was 19, his eyesight improved enough for him to complete his teaching certificate during an intense 12-week course for elementary teachers at the Academy at St. Albans, Maine.3 During this time, he spent as much as 18 hours a day studying!4

Later on, he brought that same hardcore commitment into the Millerite Movement.

Joining the Millerite Movement

James White had planned to further his education while working as a teacher. But his plans changed when he heard William Miller’s teachings about Christ’s soon return. He felt God’s call to become a preacher.

Miller’s followers, based on his interpretation of prophecies in Daniel, believed Jesus was going to return in 1844.

When James first heard William Miller’s teachings, he thought they were extreme.

You can imagine his surprise when he found out his mother had accepted the belief of the imminent Second Coming too. As he tried to object, she calmly shared passages of Scripture that worked a change in his heart. Despite his initial concerns, he too became convinced.5

Then, the Holy Spirit’s conviction set in.

James White felt God calling him to return to the town where he had been a teacher before so he could share the Second Coming message with his students’ families.

And so began his journey to become a preacher.

He purchased some publications about the Second Coming and studied them with his Bible. As 1842 rolled around, he began traveling and preaching full time.

Sometimes he faced opposition—like when a mob followed him to the venue for his meetings and threw snowballs at him through the window.6

But James White was a determined man who longed to prepare others for Jesus’ return. Within two years, he led over 1,000 people to Christ.7 He was also ordained as a minister in 1843, taking on the title Elder James White.8

So what did he do when Jesus didn’t return as expected? Let’s find out.

James White’s life after the Great Disappointment

When Jesus didn’t come on October 22, 1844 (known as the Great Disappointment), James White found comfort in the Word of God. As he and fellow Millerites, like Joseph Bates and Hiram Edson, re-studied the passages of the Bible that led them to expect Jesus’ coming, they found truths that paved the way for the formation of the Adventist Church.

What kinds of truths?

The Millerites had thought that the prophecy of Daniel 8:14, which spoke of the cleansing of the sanctuary, referred to the cleansing of the earth by fire at Jesus’ coming (2 Peter 3:11–12).

But they were wrong.

One Millerite leader, O.R.L. Crosier, went back to his Bible and came to a different conclusion:

The sanctuary referred to the heavenly sanctuary (Hebrews 8:1–2), and Jesus had begun a work of judgment there instead (Daniel 7:9–10, 13–14).

Crosier wrote an article on this topic, which James White found and read.9 As he accepted this belief, he entered a new phase of his Christian journey.

Meanwhile, he was also on the path to a new stage in life: marriage.

Marrying Ellen Harmon

James White saw Ellen Harmon for the first time in 1843 when he attended meetings in her hometown—Portland, Maine. But it wasn’t until 1845 that the two met in Orrington, Maine, when she traveled there to speak.10 He recognized that her calling came from God and volunteered to travel with her and her sister Sarah as their protector.11

The two had no plans of getting married; they felt Jesus was coming too soon for that!12

But as rumors spread about James White and Ellen Harmon traveling together, they had to make a decision. Here’s how Ellen White described it:

“He told me…he should have to go away and leave me to go with whomsoever l would, or we must be married. So we were married.”13

And that was that! Seems they just needed a little nudge to realize where their hearts were already heading.

Even though their life together began with unusual circumstances, it was evident that they loved one another deeply. James later wrote about his wife:

“We were married August 30, 1846, and from that hour to the present she has been my crown of rejoicing.”14

And Ellen White affectionately called him “the best man that ever trod shoe leather.”15

So began their life together. Along the way, they would have four children:16

- Henry Nichols (1847–1863)

- James Edson (1849–1928)

- William Clarence (1854–1937)

- John Herbert (1960, died at 3 months)

But unlike most couples who settled into the routine of home and work life, James and Ellen White knew that God had called them into ministry together. This would be a key focus of much of their life together.

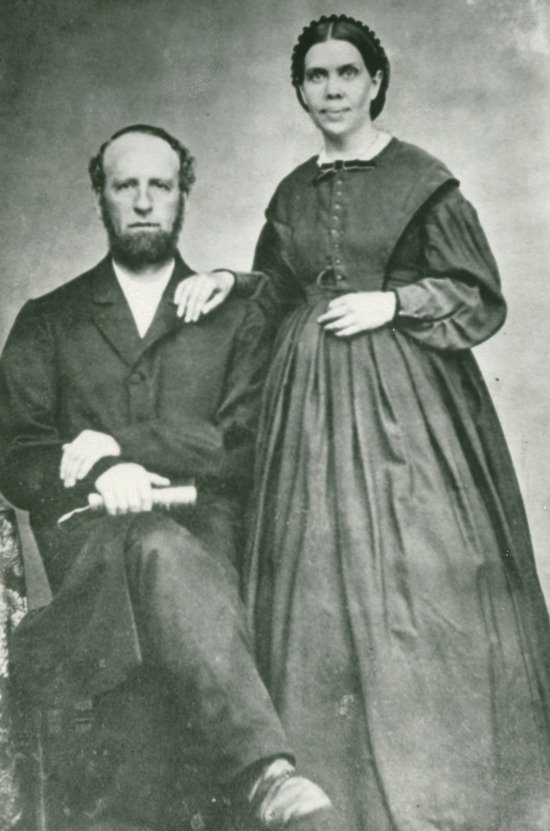

Working together with Ellen White

Courtesy of the Ellen G. White Estate, Inc.

James and Ellen White were a power team in the Adventist Church—traveling, speaking, writing, encouraging believers, and helping organize churches. Often, when they went to churches or camp meetings, James would speak and then his wife would share her message.17

He was supportive of his wife’s role, never losing faith in the messages that God gave her.

This trust was significant. As a clear thinker, he was not swayed by extreme views, and people respected him for that discernment. As a result, he was able to use his influence to show the validity of her messages.18 He also “acted vigorously to implement what she advised and what to him seemed common sense.”19

In turn, she supported him and became his strength when he hit a health crisis.

Struggling with health

Unfortunately, James White’s early struggles with health continued throughout much of his lifetime. In 1865, at only 44 years of age, he suffered his first of five strokes.

This was likely due to overwork—something science is now showing us can increase the risk of strokes and shorten a person’s life.

He was so dedicated to God’s work that he found it difficult to delegate his responsibilities. He worried that no one else would invest the same effort and energy that he had, so he pushed himself to his limits.20

In the end, he cut his own efforts short too, dying on August 6, 1881, at only 60 years old. He was buried at Oak Hill Cemetery in Battle Creek, Michigan.

Despite his short life, James White’s accomplishments went far in helping the newly forming Seventh-day Adventist Church become a solid organization.

James White’s role in the Adventist Church

James White was one of the co-founders of the Adventist Church and one of its leaders from the beginning. Both before and after marriage, he traveled, preached, and helped organize churches. He served as the president of the General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists (the highest level of church leadership) for a total of ten years.

He also filled these roles:

- Developing fundamental beliefs and incorporating the church

- Publishing

- Starting and leading church institutions

- Encouraging Adventist health reform

Let’s look at each of these in detail.

Developing fundamental beliefs and incorporating the church

James White, with his discerning and analytical mind, was a valuable asset in developing Adventist doctrine. From 1848 to 1850, he and his wife attended the first conferences of Sabbath-keeping Adventist believers. There, they earnestly studied the Bible.

James especially helped study out the following fundamental beliefs:21

- The Second Coming before the millennium

- The seventh-day Sabbath

- The state of the dead

- The three angels’ messages

- The sanctuary

- Baptism by immersion

- The prophetic gift

As the doctrines became established, he urged the church to become an official organization—something that many early Adventists opposed at first.

So what were his reasons for pushing for organization?

For one, the church needed a way to own land and institutions. They also needed a way to provide credentials for ministers and pay them.22

Ever the go-getter, James White wrote five articles in 1853 which advocated for church organization.

Over time, other church leaders saw the light in his suggestions. In October 1861, the Michigan conference was organized. And the General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists became official in 1863.

Before long, James White was pioneering the Church’s ministries and institutions, too.

Publishing

Courtesy of the Ellen G. White Estate, Inc.

Throughout his lifetime, James White was involved in publishing materials that would lead people to a deeper understanding of Bible truth.

In 1849, his wife had a vision that instructed him to start a periodical. With this counsel in mind, he began publishing the Present Truth, later known as the Second Advent Review and Sabbath Herald (the Adventist Review today).

He also began a periodical for young people, called the Youth’s Instructor.

As the publishing work grew, James and Ellen White established a press in Rochester, New York, in 1852.23 That little press became the Review and Herald Publishing Association.

Never one to settle, he started another periodical, the Signs of the Times, on the west coast in 1874. He also helped buy land for a publishing house there, starting the Pacific Press in 1875.24

Starting and managing church institutions

Besides establishing the Church itself, James White founded and led many of its institutions. These include its first school, Battle Creek College (1868), and its first health center, the Battle Creek Sanitarium. With his aptitude for business and management, he helped institutions out of financial difficulties as well.

The Review and Herald was one.

Because of sickness, he had to step down from its management for a year, and while he was gone, its financial situation plummeted. However, when he took it over again, it regained what was lost and made a profit.25

James White was large-hearted and generous, and at times he would even use his own resources to support the church’s work. He believed in the work and was determined to move it forward.

Encouraging Adventist health reform

Ellen White was convicted by the Holy Spirit about the importance of simple health principles, such as water, exercise, fresh air, sunlight, and a healthy diet. When her husband’s health took a turn for the worse in 1865, they realized the need to live out these principles.

After James’s first stroke, Ellen White took him to a health center in Dansville, New York, that specialized in water therapy and natural healing. The couple stayed there for three months, but he saw little improvement in his health.26

What to do?

Soon after, she recognized God’s calling for the church to start its own health center in Battle Creek in 1866. Unlike the center in Danville, this one would also incorporate a spiritual component and rejuvenating activity (as opposed to complete bed rest) into its program.27

As she put health reform principles into practice, she saw James improve too. But it was difficult to keep him from going back into his habits of overworking. His inability to manage his workload may well be the reason he suffered four more strokes and died young.

Though James White didn’t fully benefit from the health reforms because of his tendency to overwork, they became an important part of Adventist health teachings and went on to benefit many others.

An ardent pioneer of the Adventist Church

James White contributed to the Adventist Church in countless ways: from helping start the church, to studying its fundamental beliefs, to growing it into a denomination.

Who would have thought that such a sickly young man could do so much? He went against all odds to become a teacher, and then brought that same determination into his work for God.

He deeply loved the Bible’s truths and committed himself to the success of the Adventist Church—even at the cost of his health and life.

Related Articles

- Foster, Ray, “Elder James White,” Lest We Forget, vol. 5, no. 1, 1995. [↵]

- White, James, Life Incidents (Battle Creek, MI, Seventh-day Adventist Publishing Association, 1868), p. 12. [↵]

- Foster, “Elder James White. [↵]

- White, Life Incidents, p. 13. [↵]

- Cooper, Richard, “A Unique Partnership,” Lest We Forget, vol. 5, no. 2, 1995. [↵]

- White, James, Life Incidents, p. 77. [↵]

- Bischoff, Fred, “Qualified for the Job,” Lest We Forget, vol. 5, no. 3, 1995. [↵]

- Foster, “Elder James White”. [↵]

- Steinweg, Marlene, “James White: A Man of Action,” Lest We Forget, vol. 5, no. 3, 1995. [↵]

- White, Ellen, Christian Experience and Teachings of Ellen G. White (Pacific Press, Mountain View, CA, 1922), p. 69. [↵]

- Maxwell, C. Mervyn, Tell It to the World (Pacific Press, Nampa, ID, 1977), p. 60. [↵]

- Maxwell, p. 200. [↵]

- Steinweg, Marlene, “Her Husband’s Crown,” Lest We Forget, vol. 5, no. 2, 1995. [↵]

- White, James, Life Sketches (SDA Steam Press, Battle Creek, MI, 1880), p. 126. [↵]

- White, A. L., Ellen G. White: The Early Years: 1827–1862, vol. 1 (Review and Herald, Hagerstown, MD, 1985), p. 84. [↵]

- Ibid., p. 46. [↵]

- Cooper, Richard, “A Unique Partnership,” Lest We Forget, vol. 5, no. 2, 1995. [↵]

- Douglass, p. 53. [↵]

- VandeVere, Emmett K., “Years of Expansion, 1865–1885,” The World of Ellen G. White, p. 67, quoted in Douglass, p. 53. [↵]

- Douglass, p. 54. [↵]

- Steinweg, Marlene, “James White: A Man of Action,” Lest We Forget, Vol. 5, No. 3, 1995. [↵]

- Douglass, p. 184. [↵]

- White, James, Life Incidents, p. 293. [↵]

- Loughborough, J. N., The Great Second Advent Movement (Adventist Pioneer Library, Jasper, Oregon, 2016), p. 243. [↵]

- Maxwell, p. 200. [↵]

- Douglass, pp. 301–305. [↵]

- Ibid. [↵]

More Answers

No Results Found

The page you requested could not be found. Try refining your search, or use the navigation above to locate the post.

Didn’t find your answer? Ask us!

We understand your concern of having questions but not knowing who to ask—we’ve felt it ourselves. When you’re ready to learn more about Adventists, send us a question! We know a thing or two about Adventists.