Martin Luther. The 95 Theses. The Reformation. The Protest.

Maybe you’ve heard these terms and wondered, What’s the big deal?

The Protestant Reformation was a major religious movement that attempted to reform the church of the time—the Roman Catholic Church. Though it started in the early 1300s with John Wycliffe, many mark its official start in 1517, when Martin Luther posted his 95 Theses, protesting the corruption in the Church and its teachings. Many individuals followed Wycliffe and Luther, including Jan Hus, Jerome, Huldrych Zwingli, John Knox, and John Calvin.

So, how does the Protestant Reformation, a movement from half a millennium ago, relate to Christians today?

It all comes down to the principles that the Reformation stood for—principles like salvation by faith alone in Christ and faithfulness to Scripture above human tradition. These principles—and the right to teach and uphold them—are what the Reformers like Luther and Wycliffe stood for. And the Reformation is one of the reasons why Protestant denominations, including the Seventh-day Adventist Church, still hold onto these core Bible teachings today.

So, let’s get a bird’s eye view of the Reformation to see how these principles thread their way through it. Expect to learn:

- Factors that paved the way for the Reformation

- Key principles of the Reformation

- How the Reformation played out and influenced Christianity

Factors that paved the way for the Protestant Reformation

The Protestant Reformation didn’t simply pop onto the scene of history one day. It resulted from hundreds of years of challenge within the church, including an overemphasis on tradition and church authority and a lack of everyday access to the Scriptures.

Throughout the Middle Ages, faithful Christians sought to uphold the apostles’ teachings, but were often suppressed or discouraged because their views contradicted church leadership and tradition. Compromise went deeper and deeper as the church became more involved in politics in Western Europe.

But an important invention would make it possible for faithful Christians to speak out and spread their message more quickly. That invention was the printing press.

Here’s a little more on each of these factors:

Challenges within the church

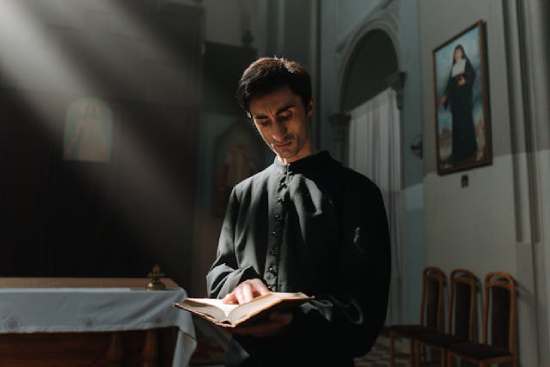

Photo by Divina Clark on Unsplash

By the 12th and 13th centuries, the official (Catholic) Church of Europe had become intertwined with the monarchies around it. And really, the church controlled the state. This kind of power, of course, led to corruption and greed among church leadership.

The secular rulers only put up with this kind of control for so long before they began to push against it. In this way, the spiritual reformation was preceded by a kind of political reformation.

England is a major example of this push-back.

On May 15, 1213, King Henry II of England gave power over his kingdom to the pope. This surrender, however, led to a protest as people pushed for their liberties. These protests resulted in the signing of the Magna Carta, which was basically a constitution that protected the people.1

Pope Innocent wasn’t quite so willing to give up control, however, and “declared the Great Charter null and void.” Church historian D’Aubigne writes that this was “the first time that the papacy came into collision with modern liberty.”2

The king was caught between the people and the pope. But the barons who had pushed for the signing of the Magna Carta, “unmoved by the insolence of the pope and the despair of the king, replied that they would maintain the charter.” As a result of their defiance, the pope excommunicated them—or kicked them out—from the church.3

D’Aubigne explains that “England had been brought low by the papacy: it rose up again by resisting Rome.”4 And that resistance had only begun.

The control and corruption of the Catholic Church at the time weren’t only political, of course; they were also spiritual. Many unbiblical practices and teachings had made their way into the belief structure over the centuries, such as:

- The worship of saints, including Mary

- The pope mediating between God and the people

- Salvation by works

- Infant baptism

Rather than teaching as Scripture does that God’s forgiveness could be received freely, the pope began to issue “pardons”—known as “indulgences” (what Luther later protested). The people could purchase these indulgences to receive forgiveness of past, present, or future sins.5

It was a money-making business to fill the church coffers and pad the pockets of church leadership.

The corruption at the top spilled also over into the orders of the monks. One line of monks, who were known as the “mendicant friars,” traveled around and begged for money, allowing them, in turn, to live in luxury.6

The overall misuse of Scripture went unnoticed by most of the common people, however, due to the next factor we’re about to discuss.

Lack of access to the Scriptures

Photo by cottonbro studio

Throughout much of the Middle Ages, the Bible wasn’t available to the common people in their own languages. This is one of the reasons why this time period is sometimes referred to as the Dark Ages—it was “dark” because few people had access to the “light” of Scripture.

Yes, there were some smaller parts of the Bible around: the Gospel of John, parts of the Old Testament, and paraphrases of the Gospels and Acts. But as D’Aubigne points out, many of these were “hidden, like theological curiosities, in the libraries of a few convents.”7

At that time, the common belief was that it was “injurious” for everyday people to read the Bible for themselves and that they needed the priests to do it on their behalf.8

As a result, many people simply accepted what the priests and church leaders told them. They considered the clergy to be the spiritual authorities. And they didn’t have a way to question the teachings or required practices of the church because they couldn’t read the Bible and know the will of God for themselves.

So, out of fear and habit, they simply followed what they were told.

What’s more, even if the Bible had been translated into their languages, it still wouldn’t have been easy to access. After all, the Bibles had to be meticulously copied by hand, and books were possessions of the wealthy—not just anyone.

All of that, though, would change with Gutenberg’s invention.

The invention of the printing press

Image by Birgit Böllinger from Pixabay

Up until the early 1400s, any kind of literature had to be copied by hand. But by the 1430s and 1440s, Gutenberg was experimenting and working on the construction of the printing press with movable type.

By 1455, he published the 42-line Bible, which became “the first book printed on a moveable type press in the West.”9

The timing was key.

A Dutch man named Erasmus, who helped to produce the first Greek New Testament,10 began using the printing press to print books in German. He envisioned that someday, the Bible would be available to the common people.11 In his own words:

“I would to God the plowman would sing a text of scripture at his plow and that the weaver at his loom would drive away the tediousness of time with it.”12

By the time Martin Luther came on the scene and began protesting the corruption of the Roman Catholic Church, he could print tracts and spread them throughout Germany and Europe.

The Bible and information about spiritual topics were becoming more widely available to the common people. People began to read the Bible for themselves and realized how much they had never been taught or had been taught incorrectly. They were hungry for truth.

This hunger for Scripture and reaction to church corruption paved the way for the key principles of the Protestant Reformation.

Key principles that spurred the Protestant Reformation

The Protestant Reformation can ultimately be condensed to five solas—the word for “only” or “alone” in Latin. These solas are:

- Sola Scriptura—Scripture alone

- Sola fide—faith alone

- Sola gratia—grace alone

- Solus Christus—Christ alone

- Soli Deo gloria—glory to God alone

The first one highlights the centrality and authority of Scripture. The Reformers longed to bring the people and the Catholic Church back to the Bible as its guide instead of continuing to rely on tradition.

The Bible was above tradition and church authority, and the test for it. If a belief or practice contradicted the Bible, then it needed to go.

The rest of the solas highlight the scriptural teaching of salvation. Salvation by grace through faith in Christ, to the glory of God.

Salvation isn’t the result of performing specific actions, obeying church traditions, or purchasing pardons for sin. As the Reformers (perhaps most famously, Martin Luther) discovered, salvation isn’t about human effort but Christ, and what He has done for us. It’s a gift of love!

These truths drove the Reformation as the Reformers realized that no church or secular authority had the right to stand between an individual and God. Everyone could have a personal and saving relationship with Jesus Christ by faith.

Even today, these principles are foundational to Protestant Christianity.

How the Reformation played out and influenced Christianity

The Reformation wasn’t a one-time event or even an exact timeline of events. It was a movement that grew slowly and then burgeoned in many different parts of Europe in the 16th century: England, Germany, Bohemia, Switzerland, Sweden, France, and more. Throughout the Western world, the principles of the Reformation were spreading with the help of the printing press and enthusiastic individuals.

The Reformation wasn’t a one-time event or even an exact timeline of events. It was a movement that grew slowly and then burgeoned in many different parts of Europe in the 16th century: England, Germany, Bohemia, Switzerland, Sweden, France, and more. Throughout the Western world, the principles of the Reformation were spreading with the help of the printing press and enthusiastic individuals.

But if we were to nail down a starting point for the Reformation, we might turn to John Wycliffe, known as “the morning star of the Reformation.”

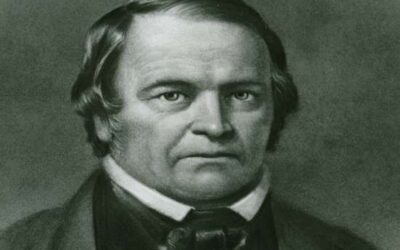

The morning star of the Reformation

John Wycliffe (c. 1330-1384) became a professor of divinity at Oxford and carried a burden to teach the Word of God. D’Aubigne writes that “he accused the clergy of having banished the Holy Scriptures and required that the authority of the word of God should be re-established in the church.”13

He pushed against the control that the papal Christian church and its traditions—such as saint worship, transubstantiation, and pilgrimages—had over the people.

The desire for people to read the Bible for themselves led him to take on the huge task of translating it—by hand!—from Latin to English, finishing the project in 1380.

His efforts and teachings would go on to impact many more.

Wycliffe’s teachings spread

Wycliffe’s followers continued to travel and preach after his death. Because many of the religious leaders of that time viewed Wycliffe’s teachings as heretical, they began to call his followers Lollards, a Dutch term meaning “mumblers” that had been used to refer to other heretical groups in the past.

But despite this bad press, Wycliffe’s teachings reached Bohemia (present-day Czech Republic) in 1400 and impacted people like Jan Hus and Jerome.14

Hus from Prague was a priest, university professor, and preacher who also had a passion to see the Bible exalted above all else.

The historian Wylie writes that Hus had “placed the Bible above the authority of Pope or Council, and thus he had entered, without knowing it, the road of Protestantism.”15

His stand for truth would lead to his burning at the stake in 1415.

About a hundred years later, another individual would rise up to become a significant figure in the Reformation.

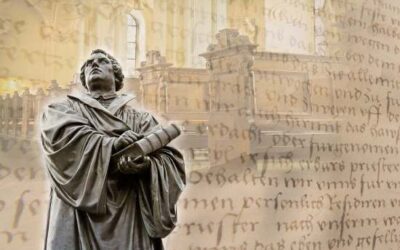

Martin Luther’s epiphany

Martin Luther never intended to start a movement—only to restore the truths of the Bible he loved.

From childhood, Luther had wrestled with a fear of God, always concerned that he needed to do something to appease God’s wrath and be assured of salvation. He thought that becoming an Augustinian monk would allow him to do that.

He did everything possible to earn salvation—rituals, ceremonies, self-denial, and even forms of self-abuse because he feared God’s condemnation so much.

But something was shifting in his mind. Luther became a professor at the University of Wittenberg and pursued his master’s in divinity. He could read the Bible in Latin, and one day, while he was teaching a course on the book of Romans, he came across Romans 1:17: “The just shall live by faith.”

Slowly, he was realizing that “there is then for the just a life different from that of other men: and this life is the gift of faith.”16

The clincher, though, came on a pilgrimage he made to Rome.

His trip was an overall disappointment, as he saw the corruption and lack of spirituality among church leaders there. During the trip, he found himself going up the famed Pilate’s Staircase on his knees to earn an indulgence that the pope had promised. Suddenly—like thunder—Romans 1:17 flashed into his mind: “The just shall live by faith.”

And at that moment, Luther realized the futility of what he was doing. Salvation was freely given to him by a loving God; all he had to do was receive it in faith.

Luther stood up, packed his bags, and left Rome soon after.

The 95 Theses

Image by Andreas Breitling from Pixabay

As the teaching of salvation by faith alone became clearer to Luther, he began to more strongly oppose the selling of indulgences. He saw the corruption connected with teaching people that they could purchase forgiveness rather than receive forgiveness and a heart change from Jesus.

Luther preached against indulgences and refused to accept them from his congregation.

And he went one step further.

Luther knew that large crowds of people would be coming to Wittenberg on November 1, 1517, All Saints Day, to tour the newly built castle church and see its relics.17

So, he wrote out 95 arguments—or theses—against indulgences and corruption within the church, nailing them to the door of the Wittenberg Church on October 31. The document was, in essence, an invitation to discuss or debate, though no one took him up on it.18 Nonetheless, Luther’s 95 Theses gained notoriety and were discussed and circulated with the help of the printing press.

The common people weren’t the only ones who took notice. Over time, Luther’s views and calls for reform created a stir among church leadership. In 1521, the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, called a special meeting—the Diet of Worms (pronounced Dee-et of Vorms)—to discuss Luther’s teachings.

At this meeting, Luther was asked to give up his teachings, which he refused to do. “Luther asserted that his conscience was captive to the Word of God and that he could not go against conscience.”19

Meanwhile, his teachings and the principles of the Reformation were gaining traction beyond Germany.

The spread of the Reformation movement

Image by Patrice Audet from Pixabay

With the help of the printing press, Luther was able to publish tracts and pamphlets, circulating the principles of salvation by faith in Christ much more easily than in times past.

Soon, the Reformation was in full swing in other countries in Europe with the efforts of individuals like:

- Huldrych Zwingli, a leader in the Swiss Reformation

- John Calvin, a leader in the French Reformation

- John Knox in Scotland

- William Tyndale in England

- Laurentius and Olaf Petri in Sweden

- Hans Taussen in Denmark

Some heard Luther teach, or they read his writings, while others simply came to the same conclusions as they began to study the Bible for themselves.

Though the Reformers never intended to separate from the church, many had no choice because of the opposition they received. As a result, the followers of these Reformers formed their own groups, which later became some of the denominations we know today.

Luther’s followers, for example, formed the Lutheran Church.

Calvin’s followers, Calvinism.

John Knox, the Presbyterian movement.

The discovery of truth continued to progress as these reformers stood up against corruption and false teachings in the church at large. Truths that had been lost during the Dark Ages were restored again.

And that’s because the Reformers were seekers of truth, desiring to follow what they found in the Bible and what God was revealing to them. They longed to see the triumph of the five solas.

Seventh-day Adventists—as do many other Protestant churches—see themselves as “heirs to the Protestant Reformation.”20 We desire to carry on the principles of the Reformation—such as Scripture alone and salvation by grace through faith in Christ alone. And we also desire to be seekers of truth, always open to new things we may find in the Word of God. It’s a principle we call “present truth.”

The path of the Reformation, though, was far from a straight path. A counter-reformation by the church at large denounced the reformers as heretics and sought to oppose their teachings.

And even the Reformers themselves sometimes missed the mark and failed to see their own blind spots. It’s for this reason that a group of people like the Anabaptists, who believed in baptism by immersion, were persecuted not only by the official church but also by other Protestants.

And for this reason, the Puritans boarded the Mayflower for the Americas to flee the control of the Protestant Church of England and be able to serve God according to conscience.

The restoration of truth in the Protestant Reformation was a journey that progressed over time. The Protestant principle of Scripture also influenced the beginning of the Seventh-day Adventist Church.

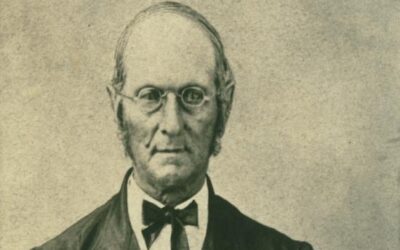

Seventh-day Adventism and the principles of the Reformation

“Courtesy of the Ellen G. White Estate, Inc.”

Seventh-day Adventism is a child of the Protestant Reformation in that it came from numerous different Protestant denominations. Those who started the Adventist Church had the same goal as the Reformers—upholding the principles of the Reformation, particularly Sola Scriptura.

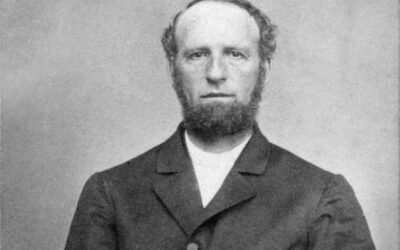

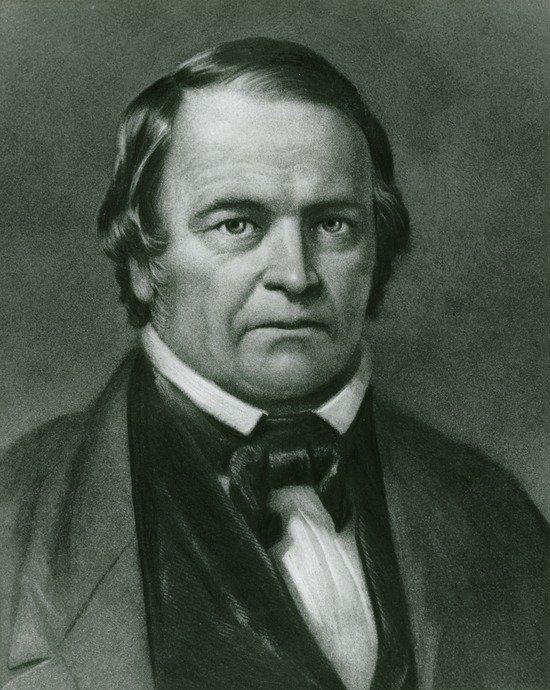

It started with William Miller, a Baptist who earnestly studied the Scripture and discovered the teaching of Jesus’ Second Coming.

Though Miller himself never became a Seventh-day Adventist, he influenced others like James and Ellen White, who were Methodists, in their quest for truth. Others joined them from Congregationalist, Baptist, Episcopalian, and Lutheran backgrounds to study the Bible and rediscover truths that hadn’t been given much study during that time, or some that had been long forgotten. Truths like:

- The seventh-day Sabbath

- Christ’s ministry in the heavenly sanctuary

- The state of a person’s existence after death

Their study all came out of a desire to hold fast to the Protestant principle of growing in the knowledge of truth.

The Reformation teaches us the value of truth

This page isn’t a full history of the Reformation; and it couldn’t possibly be, considering that volumes and volumes have been written on this topic. But the one important message we’ve seen is this:

The Reformation was all about continually seeking after truth in the Bible, the ultimate authority of the Christian.

We should never rest satisfied that we have “arrived” and don’t need to learn more. There is always more to discover about the infinite God we serve. We can continue to learn more truth that builds on existing truth.

John Robinson, a Puritan pastor who spoke to the pilgrims before they departed on the Mayflower, summarized this principle well:

“I charge you before God and His blessed angels to follow me no farther than I have followed Christ. If God should reveal anything to you by any other instrument of His, be as ready to receive it as ever you were to receive any truth of my ministry; for I am very confident the Lord hath more truth and light yet to break forth out of His holy word.”21

This emphasis on Bible study and seeking truth has been an important aspect of Adventism from its roots in the 1800s. And it continues to lead us today.

Related Articles

- D’Aubigne, J. H. Merle, History of the Reformation of the Sixteenth Century, p. 1656. [↵]

- Ibid., p. 1657. [↵]

- Ibid., p. 1658. [↵]

- Ibid. [↵]

- Wylie, James Aitken, The History of Protestantism, vol. 1, p. 539. [↵]

- D’Aubigne, p. 1665. [↵]

- Ibid., p. 1674. [↵]

- Ibid. [↵]

- “The Gutenberg Press,” Treasures of the McDonald Collection, Special Collections & Archives Research Center, Oregon State University Libraries. [↵]

- Patton, C. Michael, “Seven Historical Events that Prepared the Way for the Reformation,” Parchment and Pen. [↵]

- Little, Katherine, “Before Martin Luther, there was Erasmus – a Dutch theologian who paved the way for the Protestant Reformation,” The Conversation, Oct. 29, 2019. [↵]

- Ibid. [↵]

- D’Aubigne, pp. 1666–1667. [↵]

- Wylie, p. 277. [↵]

- Ibid., p. 283. [↵]

- D’Aubigne, p. 210. [↵]

- Wylie, pp. 540–542. [↵]

- Ibid. [↵]

- Dr. Scott Hendrix, author of Luther and the Papacy: Stages in Reformation Conflict, quoted in Coffman, Elesha, “What Luther Said,” Christianity Today, Aug. 8, 2008. [↵]

- Lemos, Felipe, “Why Should We Still Study the Protestant Reformation?” Adventist News Network, Nov. 7, 2020. [↵]

- Quoted in White, Ellen, The Great Controversy, p. 291. [↵]

More Answers

The Protestant Roots of the Seventh-day Adventist Church

Learn how the Seventh-day Adventist Church finds its roots in the Protestant Reformation. And discover what makes the pursuit of truth so integral to Protestantism.

History of the Adventist Church

After Jesus didn’t return in 1844 as many Millerites had expected, a small group rediscovered Bible truths that led them to start the Seventh-day Adventist Church in 1863. Here’s their story.

Who was J.N. Andrews and How Did He Contribute to Adventism?

John Nevins Andrews (1829–1883) was an influential leader in the early days of the Seventh-day Adventist Church. He was a Bible scholar who helped shape several Adventist beliefs and juggled many roles in the Church. Most notably, he was the first official missionary for the Adventist Church outside North America.

What Does “Adventist” Mean

Seventh-day Adventists are a Protestant Christian denomination who hold to the biblical seventh-day Sabbath. From this belief, they get the first part of their name.

William Miller

William Miller was a farmer who began a nationwide religious movement surrounding the Second Coming of Jesus. Learn about the life and legacy of this Christian pioneer.

Who Was James Springer White?

James White, a formidable co-founder of the Adventist Church, worked with his wife, Ellen White, to support, guide, and encourage this new body of believers.

Seventh-day Adventist Founders

The key figures and founders of Seventh-day Adventism were a group of people from various Protestant Christian denominations who were committed to studying the Word of God and sharing about Jesus Christ.

Joseph Bates

Joseph Bates was a sailor-turned-preacher who joined the Millerite Movement and waited for the Second Advent of Jesus to happen in 1844. Despite being disappointed when this didn’t occur, Bates held onto his faith and played an integral part in starting the Seventh-day Adventist Church.

What is the Great Disappointment and What Can We Learn From It?

The Millerites predicted Christ’s return on October 22, 1844, but Jesus never arrived. Another event took place. Discover what really happened and what the Great Disappointment can teach us today.

The Millerite Movement

William Miller’s Bible study led people to await Jesus’ Second Coming in 1844. This movement became known as the Millerite Movement and led to the Seventh-day Adventist Church.

Didn’t find your answer? Ask us!

We understand your concern of having questions but not knowing who to ask—we’ve felt it ourselves. When you’re ready to learn more about Adventists, send us a question! We know a thing or two about Adventists.